Irena Jůzová / foto Jaroslav Brabec / 2006 /

Irena Jůzová / Kolekce - Série / Collection - Series

52.bienále současného umění / Venezia / Itálie. Pod záštitou Národní galerie v Praze a Slovenskej národnej galérie ve spolupráci s Ministerstvem kultury České republiky a Ministerstvom kultúry Slovenskej republiky 10. 6. – 21. 11. 2007 Pavilon České a Slovenské republiky v areálu Giardini di Biennale v Benátkách. Otevřeno denně kromě pondělí.

Czech Republic

Collection - Series

Commissioner/ Curator

Tomáš Vlček

Coordinator

Lucie Šiklová

Organisation

National Gallery in Prague

Artist

Irena Jůzová

Collection - Series

Commissioner/ Curator

Tomáš Vlček

Coordinator

Lucie Šiklová

Organisation

National Gallery in Prague

Artist

Irena Jůzová

Irena Jůzová’s “Collection-Series”

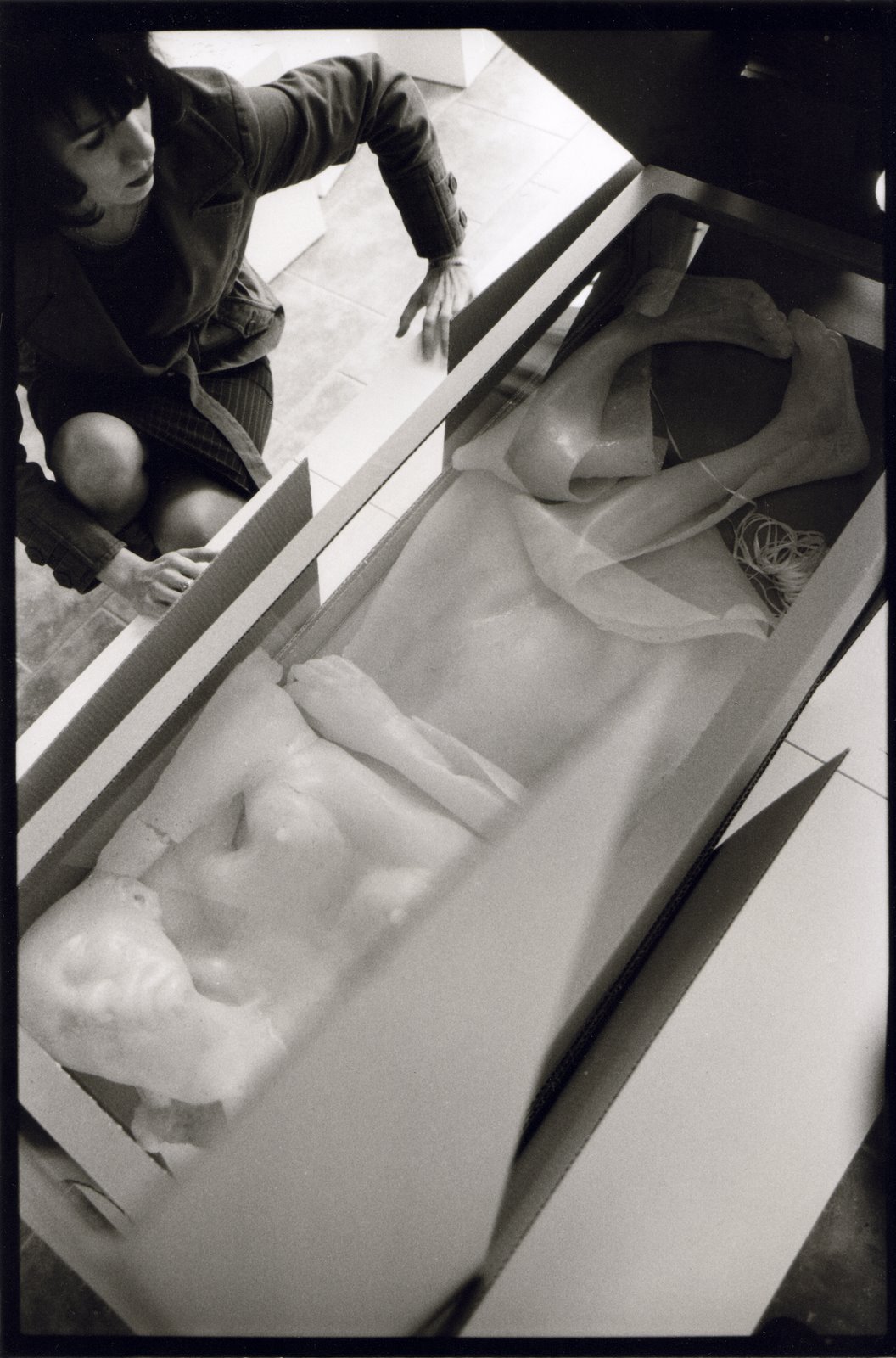

Irena Jůzová presents in the Czech and Slovak pavilion at the Venice Biennale a lukopren cast of her body. The idea to cast and exhibit the surface of one’s own body, or somebody else’s body is not new in art – what is new and significant is the input of this artist in the context of contemporary culture. In a study on Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze writes that “…we continue to produce ourselves as a subject on the basis of old modes which do not correspond to our problems.” Irena Jůzová puts her own body on exhibition, not as a sexually attractive, or topical gender motif, but as an industrial product. Evidently it is not an expression of intimacy that she is after. In her rendition, the body is stripped of attractive aesthetic and psychological motivations. The loss of all traditional connotations of the body as a subject of sexual and social relations, as the motif of an anthropological alternative within the framework of attempts to preserve life in the universe are balanced by the artist’s effort to connect (or confront) the moment of exposing her own body with the visual rendering of naked function-power, which manipulates human beings just as it manipulates works of art. This effort at self-presentation is an attempt to strip the body of certain motifs that are easily usurped by mass communication and market forces in favor of the emotions and instincts by which this form of power achieves its victory over art. In this sense the presentation of the imprint of one’s body in the context of a luxury boutique made of prefabricated paper architecture is an act of detachment, of inquiry as well as critique.

The artist herself regards exposing and reflecting on a cast of her body as a turning point in both her life and work. More than the traditional meanings of shedding one’s skin as we know them from nature and the rituals that come to terms with this phenomenon, the installation of Irena Jůzová has more to do with the definition of la pensée du dehors, the thought from outside, that is, with a paradigm of art distinct from those operating in the culture of the classical era, bound as they were to the norm of art as a metaphysical transcendence of the world of objects. Instead of metaphysics, there is fact; instead of singularity, there is mass-production. Instead of empathy, there is self-visualization. The lukopren skin bears no visible signs of a singular message, but has all the appearance of merchandise being displayed in shop-windows, and presented in industrially produced packaging. Artificial skin, “purged” of artistic connotations, thus opens the way to other meanings than those persistent in art that remains subordinate to power.

In Irena Jůzová’s work, the stripping and shedding of one’s skin has a purifying, regenerating meaning, if only in the sense that it saves the artist from the possibility, or expected obligation, of any kind of personal or artistic confession. Artificial skin is a signifier of her physical absence. All that the artist leaves behind is an imprint, the writing of a plastic text in showcases and boxes bearing the imprinted name, Irena Jůzová. She substitutes with a cast of her skin the expected, singular and physical “self” in favor of something more essential that lies between her and the contemporary world, between life and the forces that curb life today. It is a game of billiards, of sophisticated hits and misses by poetics and aesthetics in the face of the reality of the era of mass manipulation, of the production and distribution of culture as commodity.

Just as the lukopren cast is a sign of the artist’s absence, the concept of the installation in the pavilion as such is a sign of the absence of seeing architecture as the traditional structure which it purports to be. It is not made of tectonic functional elements, but serially-produced paper casts, in the shape of the architectural elements of classical structural styles. If the tectonic function in modern-day buildings is identified with art, then, as Adolf Loos put it, architecture as art in the traditional sense can realize itself only as sculpture or as tombstone. The architectonic set of Irena Jůzová’s installation draws one into its game of loss of identity and the revelations of secondary authenticity (as Milan Knížák terms one of the key features of contemporary culture). Within the setting of the Czech and Slovak pavilion, Irena Jůzová presents a game not only with the imprint of her body, but also with the imprints of architectonic elements as a daring metaphor of a memorial, or mausoleum of art as manipulated by the market.

Tomáš Vlček

Irena Jůzová presents in the Czech and Slovak pavilion at the Venice Biennale a lukopren cast of her body. The idea to cast and exhibit the surface of one’s own body, or somebody else’s body is not new in art – what is new and significant is the input of this artist in the context of contemporary culture. In a study on Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze writes that “…we continue to produce ourselves as a subject on the basis of old modes which do not correspond to our problems.” Irena Jůzová puts her own body on exhibition, not as a sexually attractive, or topical gender motif, but as an industrial product. Evidently it is not an expression of intimacy that she is after. In her rendition, the body is stripped of attractive aesthetic and psychological motivations. The loss of all traditional connotations of the body as a subject of sexual and social relations, as the motif of an anthropological alternative within the framework of attempts to preserve life in the universe are balanced by the artist’s effort to connect (or confront) the moment of exposing her own body with the visual rendering of naked function-power, which manipulates human beings just as it manipulates works of art. This effort at self-presentation is an attempt to strip the body of certain motifs that are easily usurped by mass communication and market forces in favor of the emotions and instincts by which this form of power achieves its victory over art. In this sense the presentation of the imprint of one’s body in the context of a luxury boutique made of prefabricated paper architecture is an act of detachment, of inquiry as well as critique.

The artist herself regards exposing and reflecting on a cast of her body as a turning point in both her life and work. More than the traditional meanings of shedding one’s skin as we know them from nature and the rituals that come to terms with this phenomenon, the installation of Irena Jůzová has more to do with the definition of la pensée du dehors, the thought from outside, that is, with a paradigm of art distinct from those operating in the culture of the classical era, bound as they were to the norm of art as a metaphysical transcendence of the world of objects. Instead of metaphysics, there is fact; instead of singularity, there is mass-production. Instead of empathy, there is self-visualization. The lukopren skin bears no visible signs of a singular message, but has all the appearance of merchandise being displayed in shop-windows, and presented in industrially produced packaging. Artificial skin, “purged” of artistic connotations, thus opens the way to other meanings than those persistent in art that remains subordinate to power.

In Irena Jůzová’s work, the stripping and shedding of one’s skin has a purifying, regenerating meaning, if only in the sense that it saves the artist from the possibility, or expected obligation, of any kind of personal or artistic confession. Artificial skin is a signifier of her physical absence. All that the artist leaves behind is an imprint, the writing of a plastic text in showcases and boxes bearing the imprinted name, Irena Jůzová. She substitutes with a cast of her skin the expected, singular and physical “self” in favor of something more essential that lies between her and the contemporary world, between life and the forces that curb life today. It is a game of billiards, of sophisticated hits and misses by poetics and aesthetics in the face of the reality of the era of mass manipulation, of the production and distribution of culture as commodity.

Just as the lukopren cast is a sign of the artist’s absence, the concept of the installation in the pavilion as such is a sign of the absence of seeing architecture as the traditional structure which it purports to be. It is not made of tectonic functional elements, but serially-produced paper casts, in the shape of the architectural elements of classical structural styles. If the tectonic function in modern-day buildings is identified with art, then, as Adolf Loos put it, architecture as art in the traditional sense can realize itself only as sculpture or as tombstone. The architectonic set of Irena Jůzová’s installation draws one into its game of loss of identity and the revelations of secondary authenticity (as Milan Knížák terms one of the key features of contemporary culture). Within the setting of the Czech and Slovak pavilion, Irena Jůzová presents a game not only with the imprint of her body, but also with the imprints of architectonic elements as a daring metaphor of a memorial, or mausoleum of art as manipulated by the market.

Tomáš Vlček

Kolekce-Série Ireny Jůzové

Irena Jůzová vystavuje v Česko-slovenském pavilonu Benátského bienále lukoprenový odlitek svého těla. Myšlenka odlít a vystavit povrch vlastního těla, nebo těla někoho jiného není v umění nová, nový a podstatný je vstup této autorky do kontextu současné kultury.Gilles Deleuze v studii o Foucaultovi napsal:,,…stále produkujeme sebe jako subjekty, podle starých způsobů, které už neodpovídají našim problémům…“. Irena Jůzová exhibuje své vlastní tělo,nikoliv jako sexuálně atraktivní, nebo dobově aktuální generový motiv, ale jako průmyslový produkt. Očividně jí nejde o expresi intimity. Tělo v jejím pojetí je zbavováno atraktivních a psychologických motivací. Všechny ztráty tradičních konotací těla jako tématu sexuálních a sociálních vztahů, jako motivu antropologické alternativy v rámci pokusů o uchování života ve vesmíru jsou vyvažovány pokusem autorky spojit, či konfrontovat moment odhalení vlastního těla se zviditelněním vypreparované funkce-moci, která manipuluje stejně lidské bytosti jako umělecká díla.Úsilí o prezentaci sama sebe je pokusem o zbavování těla motivů, kterých se snadno zmocňuje masová komunikace a trh s city a pudy, jimiž moc dosahuje svého vítězství nad uměním. V tomto smyslu je prezentování otisku vlastního těla v prostředí exklusivního butiku tvořeného prefabrikovanými výlisky papírové architektury činem odstupu, tázání i kritiky.

Autorka sama vnímá odhalení a reflexi odlitku svého těla jako přelomovou událost svého života i díla. Více než s tradičními významy zbavování se kůže,které známe z přírody a z rituálů, které se s ní vyrovnávají, má instalace Ireny Jůzové co dělat s definicí myšlení vnějšku, tedy s jiným řádem tvorby nežli znala kultura klasické doby vázaná k normě umění jako metafyzického překročení předmětné skutečnosti. Místo metafyziky je zde věcnost, místo jedinečnosti sériovost, místo vcítění zviditelnění. Lukoprenová kůže nemá žádné zjevné znaky jedinečného poselství, má podobu zboží, které se vystavuje v prodejních vitrínách a skládá se do průmyslově vyráběných obalů. Umělá kůže ,,očistěná“ od uměleckých konotací otevírá cestu k jiným obsahům, než jaké přetrvávají v umění podřizujícímu se moci.

Svlékání z kůže a odhazování kůže má v tvorbě Ireny Jůzové očistný, či obrodný význam, už tím, že zachraňuje autorku před možností, či očekávanou povinností jakéhokoliv jejího osobního, či tvůrčího doznání. Umělá kůže je znakem její fyzické nepřítomnosti. Autorka zanechává po sobě jen otisk, rukopis plastického textu vložený do vitrín a krabic potištěných jménem, Irena Jůzová. Nahrazuje odlitkem své kůže očekávané, jednotlivé fyzické já ve prospěch čehosi podstatnějšího co je mezi ní a současným světem, mezi životem a silami, které dnes život ohraničují. Je to biliárová hra promyšlených nárazů a míjení poetika a estetik tváří v tvář skutečnosti doby masové manipulace, produkce a distribuce kultury jako zboží.

Tak jako je lukoprenový odlitek kůže znakem nepřítomnosti autorky, je i celá koncepce instalace pavilonu znakem nepřítomnosti pojetí architektury jako klasické stavby, za jakou se vydává. Jejím materiálem nejsou tektonicky funkční prvky, ale sériově vyrobené papírové výlisky ve tvarech architektonických článků klasických stavebních řádů. Jestli-že tektonická funkce ve stavbách moderní doby se ztotožňuje s uměním, pak jak to vyjádřil Adolf Loos, architektura jako umění v tradičním slova smyslu se může realizovat jen bud´ jako plastika nebo jako náhrobek. Instalace Ireny Jůzové vtahuje architektonickou kulisou do své hry ztrát identity a objevů sekundární autentičnosti ( jak jeden z podstatných rysů současné kultury nazývá Milan Knížák). Irena Jůzová představuje na scéně Česko-slovenského pavilonu nejen hru s otiskem vlastního těla, ale i s otisky architektonických prvků jako odvážnou metaforu pomníku, či mauzolea umění zmanipulovaného trhem.

Tomáš Vlček

Irena Jůzová vystavuje v Česko-slovenském pavilonu Benátského bienále lukoprenový odlitek svého těla. Myšlenka odlít a vystavit povrch vlastního těla, nebo těla někoho jiného není v umění nová, nový a podstatný je vstup této autorky do kontextu současné kultury.Gilles Deleuze v studii o Foucaultovi napsal:,,…stále produkujeme sebe jako subjekty, podle starých způsobů, které už neodpovídají našim problémům…“. Irena Jůzová exhibuje své vlastní tělo,nikoliv jako sexuálně atraktivní, nebo dobově aktuální generový motiv, ale jako průmyslový produkt. Očividně jí nejde o expresi intimity. Tělo v jejím pojetí je zbavováno atraktivních a psychologických motivací. Všechny ztráty tradičních konotací těla jako tématu sexuálních a sociálních vztahů, jako motivu antropologické alternativy v rámci pokusů o uchování života ve vesmíru jsou vyvažovány pokusem autorky spojit, či konfrontovat moment odhalení vlastního těla se zviditelněním vypreparované funkce-moci, která manipuluje stejně lidské bytosti jako umělecká díla.Úsilí o prezentaci sama sebe je pokusem o zbavování těla motivů, kterých se snadno zmocňuje masová komunikace a trh s city a pudy, jimiž moc dosahuje svého vítězství nad uměním. V tomto smyslu je prezentování otisku vlastního těla v prostředí exklusivního butiku tvořeného prefabrikovanými výlisky papírové architektury činem odstupu, tázání i kritiky.

Autorka sama vnímá odhalení a reflexi odlitku svého těla jako přelomovou událost svého života i díla. Více než s tradičními významy zbavování se kůže,které známe z přírody a z rituálů, které se s ní vyrovnávají, má instalace Ireny Jůzové co dělat s definicí myšlení vnějšku, tedy s jiným řádem tvorby nežli znala kultura klasické doby vázaná k normě umění jako metafyzického překročení předmětné skutečnosti. Místo metafyziky je zde věcnost, místo jedinečnosti sériovost, místo vcítění zviditelnění. Lukoprenová kůže nemá žádné zjevné znaky jedinečného poselství, má podobu zboží, které se vystavuje v prodejních vitrínách a skládá se do průmyslově vyráběných obalů. Umělá kůže ,,očistěná“ od uměleckých konotací otevírá cestu k jiným obsahům, než jaké přetrvávají v umění podřizujícímu se moci.

Svlékání z kůže a odhazování kůže má v tvorbě Ireny Jůzové očistný, či obrodný význam, už tím, že zachraňuje autorku před možností, či očekávanou povinností jakéhokoliv jejího osobního, či tvůrčího doznání. Umělá kůže je znakem její fyzické nepřítomnosti. Autorka zanechává po sobě jen otisk, rukopis plastického textu vložený do vitrín a krabic potištěných jménem, Irena Jůzová. Nahrazuje odlitkem své kůže očekávané, jednotlivé fyzické já ve prospěch čehosi podstatnějšího co je mezi ní a současným světem, mezi životem a silami, které dnes život ohraničují. Je to biliárová hra promyšlených nárazů a míjení poetika a estetik tváří v tvář skutečnosti doby masové manipulace, produkce a distribuce kultury jako zboží.

Tak jako je lukoprenový odlitek kůže znakem nepřítomnosti autorky, je i celá koncepce instalace pavilonu znakem nepřítomnosti pojetí architektury jako klasické stavby, za jakou se vydává. Jejím materiálem nejsou tektonicky funkční prvky, ale sériově vyrobené papírové výlisky ve tvarech architektonických článků klasických stavebních řádů. Jestli-že tektonická funkce ve stavbách moderní doby se ztotožňuje s uměním, pak jak to vyjádřil Adolf Loos, architektura jako umění v tradičním slova smyslu se může realizovat jen bud´ jako plastika nebo jako náhrobek. Instalace Ireny Jůzové vtahuje architektonickou kulisou do své hry ztrát identity a objevů sekundární autentičnosti ( jak jeden z podstatných rysů současné kultury nazývá Milan Knížák). Irena Jůzová představuje na scéně Česko-slovenského pavilonu nejen hru s otiskem vlastního těla, ale i s otisky architektonických prvků jako odvážnou metaforu pomníku, či mauzolea umění zmanipulovaného trhem.

Tomáš Vlček

One of the most defining phenomena of the post-modern era is the fact that the world of art has accepted the principles of the free market. These have been adopted not only in terms of trading in works of art, but in all areas. The very inception of a work of art is subject to these laws, both in the role of the artist, the hunger for fresh goods, the managerial role of art theoreticians, and so forth. The atmosphere of the art scene is undistinguishable from that of the commodity market in consumer goods.

Though a work of art is in some sense a commodity, this is true only in certain very partial aspects. It can be commissioned, or sold, and can even function as a form of financial capital, but on the other hand this is not what a work of art is, essentially, as the value of a work of art cannot be established. Let me cite an example: the value of gold is established based on its degree of fineness, the quality of meat or vegetables is determined by their freshness or type; in other words, by measurable and qualitative parameters. A painting – such as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers – is just a piece of canvas of mean quality, covered with paint that has moreover been subject to the ravages of time, so that today the painting is different than when it first emerged from the artist’s studio. The price for a piece of canvas smeared with paint is the price of the faith that we entrust in this object, for a certain hope that this relic gives us, even if this hope does not spring from the reality of the artifact, but from a haze of notions that cannot be measured.

This lengthy and seemingly irrelevant introduction is necessary to enter into thinking about Irena Jůzová’s work – entitled “Collection-Series.” The resulting object the artist puts before us is a shop – a traditional commercial space filled with standard furniture and boxes with merchandise. A shop of this kind could sell pretty much anything – but most likely some kind of luxury goods. But now it strikes me that what the artist is offering is in fact highly luxury merchandise. In this market form she offers a part of her private and very individual Self. She thus creates casts of the skin of her own body, almost indistinguishable from real skin, offering these for sale, or at least presenting them as items for sale. Flaunting one’s privacy has long been common practice in both Modernist and post-modern art. I cannot resist quoting the notorious bon mot about the Romantic Czech 19th century poet Karel Hynek Mácha, who kept very open private diaries. After these were published – this naturally did not happen until the late 20th century – one theoretician commented, that today Mácha would have presented his secret texts publicly, while he would have kept his lyrical poems secret in his diary.

We must also note, that even though the artist offers herself – it is only the surface of her physical being. She consistently keeps the rest of her personality to herself.

Post-modern art has brought a fascination with the surface as the final product. The surface began to play the role of something comprehensive. Still, I do not believe that Irena Jůzová takes this aspect into account, she merely as it were repeats the early ritual of the snake shedding its skin, or the human ritual of undressing the virgin, and instead of accentuating the snake in its new skin, or the virgin in her new role, she offers us only the discarded shells. In order to make them desirable, however, she accordingly adjusts these skins, offering them as she does for sale in a chic boutique that could easily be at home on Sunset Boulevard or the Champs-Elysées.

In a sense, it is a parallel to the situation in art, where there exists the all-mighty taste of the mainstream, which wants to take possession of anything that promises to become a commodity on some kind of a market, whether this be the financial market, or the market of ideas, curiosities and surprises. In this work, Irena Jůzová clearly demonstrates that despite luxurious packaging, we purchase mostly (or in fact perhaps always) only the surface, in her case an industrialized copy of a surface. It is a strange kind of deception, as if an exhibitionist was flashing a prosthetic member. Would such an exhibitionist be persecuted?

The reality of the contemporary world is multilayered – at least this is how the post-modern individual experiences it. Very often, a single layer is seen as representative of the whole, or as the whole itself. Jůzová endeavors to avoid this kind of simplified perspective. Right from the start we are aware that the product she offers is authentic only secondarily. It comes to mind that it is in fact secondary authenticity that is typical for the world today – only I am at a loss how to define this secondary authenticity. And it is perhaps in the world without definitions that art dwells, and so does the work of Irena Jůzová, as presented at the Biennale in Venice.

Milan Knížák

Though a work of art is in some sense a commodity, this is true only in certain very partial aspects. It can be commissioned, or sold, and can even function as a form of financial capital, but on the other hand this is not what a work of art is, essentially, as the value of a work of art cannot be established. Let me cite an example: the value of gold is established based on its degree of fineness, the quality of meat or vegetables is determined by their freshness or type; in other words, by measurable and qualitative parameters. A painting – such as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers – is just a piece of canvas of mean quality, covered with paint that has moreover been subject to the ravages of time, so that today the painting is different than when it first emerged from the artist’s studio. The price for a piece of canvas smeared with paint is the price of the faith that we entrust in this object, for a certain hope that this relic gives us, even if this hope does not spring from the reality of the artifact, but from a haze of notions that cannot be measured.

This lengthy and seemingly irrelevant introduction is necessary to enter into thinking about Irena Jůzová’s work – entitled “Collection-Series.” The resulting object the artist puts before us is a shop – a traditional commercial space filled with standard furniture and boxes with merchandise. A shop of this kind could sell pretty much anything – but most likely some kind of luxury goods. But now it strikes me that what the artist is offering is in fact highly luxury merchandise. In this market form she offers a part of her private and very individual Self. She thus creates casts of the skin of her own body, almost indistinguishable from real skin, offering these for sale, or at least presenting them as items for sale. Flaunting one’s privacy has long been common practice in both Modernist and post-modern art. I cannot resist quoting the notorious bon mot about the Romantic Czech 19th century poet Karel Hynek Mácha, who kept very open private diaries. After these were published – this naturally did not happen until the late 20th century – one theoretician commented, that today Mácha would have presented his secret texts publicly, while he would have kept his lyrical poems secret in his diary.

We must also note, that even though the artist offers herself – it is only the surface of her physical being. She consistently keeps the rest of her personality to herself.

Post-modern art has brought a fascination with the surface as the final product. The surface began to play the role of something comprehensive. Still, I do not believe that Irena Jůzová takes this aspect into account, she merely as it were repeats the early ritual of the snake shedding its skin, or the human ritual of undressing the virgin, and instead of accentuating the snake in its new skin, or the virgin in her new role, she offers us only the discarded shells. In order to make them desirable, however, she accordingly adjusts these skins, offering them as she does for sale in a chic boutique that could easily be at home on Sunset Boulevard or the Champs-Elysées.

In a sense, it is a parallel to the situation in art, where there exists the all-mighty taste of the mainstream, which wants to take possession of anything that promises to become a commodity on some kind of a market, whether this be the financial market, or the market of ideas, curiosities and surprises. In this work, Irena Jůzová clearly demonstrates that despite luxurious packaging, we purchase mostly (or in fact perhaps always) only the surface, in her case an industrialized copy of a surface. It is a strange kind of deception, as if an exhibitionist was flashing a prosthetic member. Would such an exhibitionist be persecuted?

The reality of the contemporary world is multilayered – at least this is how the post-modern individual experiences it. Very often, a single layer is seen as representative of the whole, or as the whole itself. Jůzová endeavors to avoid this kind of simplified perspective. Right from the start we are aware that the product she offers is authentic only secondarily. It comes to mind that it is in fact secondary authenticity that is typical for the world today – only I am at a loss how to define this secondary authenticity. And it is perhaps in the world without definitions that art dwells, and so does the work of Irena Jůzová, as presented at the Biennale in Venice.

Milan Knížák

Jedním z nejvýraznějších fenoménů postmoderní doby je skutečnost, že svět umění přijal principy trhu. Tyto principy přijal nejen v obchodě s uměleckými díly, ale ve všech oblastech. Již vznik uměleckého díla je těmto zákonům podřízen, a to jak postavením umělce, zájmem o čerstvé zboží, manažerskou rolí teoretiků, atd.

Klima umělecké sféry je nerozlišitelné od klimatu trhu se spotřebním zbožím.Umělecké dílo je sice spotřebním zbožím, ale jen v určitém, a to velmi parciálním aspektu. Může být objednáváno, prodáváno, může být finanční jistinou, ale na druhé straně tím v podstatě není, poněvadž hodnota není u uměleckých děl stanovitelná. Uvedu příklad: cena zlata se počítá podle ryzosti, kvalita masa a zeleniny je určována stářím, druhem, tedy měřitelnými kvalitativními parametry. Obraz, například Goghovi Slunečnice, je jen kusem nepříliš kvalitního plátna pokrytém barvami, které navíc čas změnil, a tak obraz je dnes jiný, než jak vyšel z umělcovy dílny. Cena barvami pomazaného kusu plátna je cenou za naši víru, kterou v tento objekt vkládáme, za určitou naději, kterou nám tato relikvie poskytuje, i když tato naděje nevyvěrá z reálu díla, ale z oparu bez parametrů.

Tento dlouhý a zdánlivě odtažitý úvod potřebuji k tomu, abych nastartoval přemýšlení o díle Ireny Jůzové ,, Kolekce – Série,,.Výsledným objektem, který autorka předkládá, je prodejna, klasický obchodní prostor zaplněný prodejním nábytkem a krabicemi se zbožím. V takovémto obchodě by mohlo být prodáváno v podstatě cokoliv, nejspíš však luxusní zboží. Ted´ mě však napadá, že to, co umělkyně nabízí, je velmi luxusní zboží. Chce touto tržní formou nabízet něco ze svého soukromého a velmi individuálního Já. Proto vytváří od pravé kůže téměř nerozeznatelné odlitky slupek jejího těla a ty nabízí k prodeji či je alespoň prezentuje jako prodejní artikl. Stavět své soukromí na odiv je v moderním i postmoderním umění již dlouho obvyklé.

Nemohu neuvést známý bonmot o romantickém básníku Karlu Hynku Máchovi, který si psal velmi otevřené deníky. Po jejich publikování, samozřejmě až v druhé polovině 20.století, jeden z teoretiků prohlásil, že dnes by Mácha prezentoval na veřejnosti své tajné texty a lyrické básně tajil v deníku.Je také nutné si všimnout, že umělkyně sice nabízí sebe samu, ale jen povrch své fyzické stránky. Zbytek své osobnosti důsledně tají.

Postmoderní umění přineslo zájem o povrch jako o finální produkt.Povrch začal hrát roli něčeho komplexního. Nemyslím však, že Irena Jůzová brala tento aspekt v úvahu, jen jakoby opakovala každoroční rituál svlékání hada či lidský rituál svlékání panny, a místo, aby kladla důraz na hada v nové kůži a pannu v nové roli, předkládá nám odhozené slupky. Ovšem právě tyto slupky, aby byly žádoucí, vhodně adjustuje, a nabízí je k prodeji v kvalitním butiku, který by mohl stát na Sunset Boulevard nebo Champs Ellysée.

Je to svým způsobem paralela se situací v umění, kde existuje všemocný střední proud, který se chce zmocnit všeho, co má naději stát se objektem nějakého trhu a nezáleží, zda jde o trh finanční nebo trh nápadů, kuriozit a překvapení. Irena Jůzová tímto svým dílem jasně demonstruje, že v přepychové ambaláži kupujeme většinou ( a vlastně vždy) jen povrch a v jejím případě ještě v industrializované kopii. Je to zvláštní druh podvodu. Jakoby obnažujícímu se exhibicionistovi visel z kalhot umělý úd. Byl by takový exhibicionista stíhán?Současná realita je mnohovrstevnatá, alespoň tak si ji postmoderní člověk uvědomuje. Velmi často je jediná vrstva vnímána jako reprezentant celku či celek sám. Tomuto zjednodušenému pohledu se chce Jůzová vyhnout. Od začátku víme, že nabízený produkt je autentický pouze sekundárně.

Napadá mě, že právě sekundární autenticita je typická pro současný svět, jen neumím tuto sekundární autenticitu definovat. A možná, že právě ve světě bez definic se nalézá umění, a tedy i dílo Ireny Jůzové prezentované na Benátském Bienále.

Milan Knížák

Klima umělecké sféry je nerozlišitelné od klimatu trhu se spotřebním zbožím.Umělecké dílo je sice spotřebním zbožím, ale jen v určitém, a to velmi parciálním aspektu. Může být objednáváno, prodáváno, může být finanční jistinou, ale na druhé straně tím v podstatě není, poněvadž hodnota není u uměleckých děl stanovitelná. Uvedu příklad: cena zlata se počítá podle ryzosti, kvalita masa a zeleniny je určována stářím, druhem, tedy měřitelnými kvalitativními parametry. Obraz, například Goghovi Slunečnice, je jen kusem nepříliš kvalitního plátna pokrytém barvami, které navíc čas změnil, a tak obraz je dnes jiný, než jak vyšel z umělcovy dílny. Cena barvami pomazaného kusu plátna je cenou za naši víru, kterou v tento objekt vkládáme, za určitou naději, kterou nám tato relikvie poskytuje, i když tato naděje nevyvěrá z reálu díla, ale z oparu bez parametrů.

Tento dlouhý a zdánlivě odtažitý úvod potřebuji k tomu, abych nastartoval přemýšlení o díle Ireny Jůzové ,, Kolekce – Série,,.Výsledným objektem, který autorka předkládá, je prodejna, klasický obchodní prostor zaplněný prodejním nábytkem a krabicemi se zbožím. V takovémto obchodě by mohlo být prodáváno v podstatě cokoliv, nejspíš však luxusní zboží. Ted´ mě však napadá, že to, co umělkyně nabízí, je velmi luxusní zboží. Chce touto tržní formou nabízet něco ze svého soukromého a velmi individuálního Já. Proto vytváří od pravé kůže téměř nerozeznatelné odlitky slupek jejího těla a ty nabízí k prodeji či je alespoň prezentuje jako prodejní artikl. Stavět své soukromí na odiv je v moderním i postmoderním umění již dlouho obvyklé.

Nemohu neuvést známý bonmot o romantickém básníku Karlu Hynku Máchovi, který si psal velmi otevřené deníky. Po jejich publikování, samozřejmě až v druhé polovině 20.století, jeden z teoretiků prohlásil, že dnes by Mácha prezentoval na veřejnosti své tajné texty a lyrické básně tajil v deníku.Je také nutné si všimnout, že umělkyně sice nabízí sebe samu, ale jen povrch své fyzické stránky. Zbytek své osobnosti důsledně tají.

Postmoderní umění přineslo zájem o povrch jako o finální produkt.Povrch začal hrát roli něčeho komplexního. Nemyslím však, že Irena Jůzová brala tento aspekt v úvahu, jen jakoby opakovala každoroční rituál svlékání hada či lidský rituál svlékání panny, a místo, aby kladla důraz na hada v nové kůži a pannu v nové roli, předkládá nám odhozené slupky. Ovšem právě tyto slupky, aby byly žádoucí, vhodně adjustuje, a nabízí je k prodeji v kvalitním butiku, který by mohl stát na Sunset Boulevard nebo Champs Ellysée.

Je to svým způsobem paralela se situací v umění, kde existuje všemocný střední proud, který se chce zmocnit všeho, co má naději stát se objektem nějakého trhu a nezáleží, zda jde o trh finanční nebo trh nápadů, kuriozit a překvapení. Irena Jůzová tímto svým dílem jasně demonstruje, že v přepychové ambaláži kupujeme většinou ( a vlastně vždy) jen povrch a v jejím případě ještě v industrializované kopii. Je to zvláštní druh podvodu. Jakoby obnažujícímu se exhibicionistovi visel z kalhot umělý úd. Byl by takový exhibicionista stíhán?Současná realita je mnohovrstevnatá, alespoň tak si ji postmoderní člověk uvědomuje. Velmi často je jediná vrstva vnímána jako reprezentant celku či celek sám. Tomuto zjednodušenému pohledu se chce Jůzová vyhnout. Od začátku víme, že nabízený produkt je autentický pouze sekundárně.

Napadá mě, že právě sekundární autenticita je typická pro současný svět, jen neumím tuto sekundární autenticitu definovat. A možná, že právě ve světě bez definic se nalézá umění, a tedy i dílo Ireny Jůzové prezentované na Benátském Bienále.

Milan Knížák

ATELIÉR / 18 / 2007 / strana 8 / Co mi nejvíce utkvělo v mysli? / Jiří Valoch

Česko-slovenký pavilon, zdá se, byl, myslím, přijat dobře. Irena Jůzová ( 1965 ) reprezentovala umění subtilní, mírně reflektující vlastní tělovost a zároveń zaujala jakousi architektonickou monumentalitou bílých a skleněných forem. Dobře souzněla s dispozicemi pavilonku a dávala celku možný transcendentální přesah - již tím se příjemně lišila od řady pavilonů a snad i korespondovala s tématem ročníku. / výńatek z obsáhlého textu /

Curriculum vitae

Irena Jůzová (1965) graduated from the School of Monumental at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague ( 1990 -1994) where she worked as assistant professor in the years 1995 – 2006. Since 2006, she has been a consultant at the Faculty of Multi-Media Communications at the Tomáš Bata University in Zlín.As a student she won several prizes from her studio at the Academy of Fine Arts, and participated in a number of exhibitions. In 1992, she won a prize at the European Biennale of Young Artist Germinations 7 in Grenoble ( Francie), for her interactive work Stůl pro dvacet hráčů ( Table for Twenty Players).In 1993, the Academy of Fine Arts selected her to participate at the 4 th Biennial of European Academies of Visual Arts, in Maastricht. In 1992 she originated the legendary Ženské domovy ( Womens Housing) exhibition together with Štěpánka Šimlová, Veronika Bromová, Kateřina Vincourová,Markéta Othová a Ellen Řádová.She was had a number solo exhibitions, such as Vysílač ( Transmitter, Gallery of Modern Arts, Hradec Králové,2000), Metropolitan Mystify ( The White Unicorn Gallery, Klatovy,2003),Find Your Style...( Caesar Gallery, Olomouc,2004),Drawings (Kabinet Gallery, Brno, 2005), and Metropolitan Reality ( Wortner House, AJG,České Budějovice, 2005).She received a scholarship from Jana and Milan Jelinek Foundation.Her work entitled Místa I. / Places I.( an interactive installation) supported by this foundation was presented in 1997 at Media Art Biennale WRO 97 in Wroclaw, and forms part of the collections of the National Gallery in Prague.Irena Jůzová has received a number of scholarships and has participated in many artist –in residence projects, among them Sculpture Space, INC.,NY,USA, Arts Links Residencies, LBMA Video Annex, Museum of Art Long Beach, CA,USA and Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France in 2001.She presented Czech and Slovak Republics on 52.la Biennale di Venezia in 2007.

Irena Jůzová (1965) graduated from the School of Monumental at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague ( 1990 -1994) where she worked as assistant professor in the years 1995 – 2006. Since 2006, she has been a consultant at the Faculty of Multi-Media Communications at the Tomáš Bata University in Zlín.As a student she won several prizes from her studio at the Academy of Fine Arts, and participated in a number of exhibitions. In 1992, she won a prize at the European Biennale of Young Artist Germinations 7 in Grenoble ( Francie), for her interactive work Stůl pro dvacet hráčů ( Table for Twenty Players).In 1993, the Academy of Fine Arts selected her to participate at the 4 th Biennial of European Academies of Visual Arts, in Maastricht. In 1992 she originated the legendary Ženské domovy ( Womens Housing) exhibition together with Štěpánka Šimlová, Veronika Bromová, Kateřina Vincourová,Markéta Othová a Ellen Řádová.She was had a number solo exhibitions, such as Vysílač ( Transmitter, Gallery of Modern Arts, Hradec Králové,2000), Metropolitan Mystify ( The White Unicorn Gallery, Klatovy,2003),Find Your Style...( Caesar Gallery, Olomouc,2004),Drawings (Kabinet Gallery, Brno, 2005), and Metropolitan Reality ( Wortner House, AJG,České Budějovice, 2005).She received a scholarship from Jana and Milan Jelinek Foundation.Her work entitled Místa I. / Places I.( an interactive installation) supported by this foundation was presented in 1997 at Media Art Biennale WRO 97 in Wroclaw, and forms part of the collections of the National Gallery in Prague.Irena Jůzová has received a number of scholarships and has participated in many artist –in residence projects, among them Sculpture Space, INC.,NY,USA, Arts Links Residencies, LBMA Video Annex, Museum of Art Long Beach, CA,USA and Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France in 2001.She presented Czech and Slovak Republics on 52.la Biennale di Venezia in 2007.

Irena Jůzová (1965) je absolventkou Akademie výtvarných umění v Praze, Školy monumentální tvorby (1990 – 1994) profesora Aleše Veselého, kde pak byla od roku 1995 do 2006 odbornou asistentkou. Od roku 2006 působí jako odborná konzultantka v Ateliéru prostorové tvorby na Fakultě multimediálních komunikací Univerzity Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně. Během studia získala několik ateliérových cen AVU a zúčastnila se řady výstav. V roce 1992 na European Biennale of Young Artists Germination 7 v Grenoblu obdržela cenu za interaktivní práci Stůl pro dvacet hráčů. V roce 1993 byla vybrána Akademií výtvarných umění k účasti na 4 Biennale European Academies of Visual Arts v Maastrichtu. Roku 1992 stála u zrodu legendárních Ženských domovů spolu se Štěpánkou Šimlovou, Veronikou Bromovou, Kateřinou Vincourovou, Markétou Othovou a Elen Řádovou. Se svými aktuálními pracemi se představila na samostatných výstavách, např. Vysílač (Galerie moderního umění v Hradci Králové, 2000), Metropolitan Mystify (Galerie U Bílého jednorožce, Klatovy, 2003), Find Your Style... (Galerie Caesar, Olomouc, 2004), Kresby (Galerie Kabinet, Brno, 2005) a Metropolitan Reality (Wortnerův dům AJG, České Budějovice, 2005). Patří ke stipendistům podpořeným nadací Jana & Milan Jelinek Foundation. Za podpory této nadace bylo její dílo Místa I. (interaktivní instalace) vystaveno v roce 1997 na Media Art Biennale WRO 97 ve Wroclavi a je součástí sbírek Národní galerie v Praze. Umělkyně je zastoupena dále v Uměleckoprůmyslovém museu v Praze, v Galerii moderního umění v Hradci Králové a soukromých sbírkách. Získala řadu stipendií a zúčastnila se řady rezidenčních pobytů, např. Sculpture Space, INC., NY, USA, Arts Links Residencies of LBMA Video Annex, Museum of Art Long Beach, CA, USA a Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris.